Negotiated Consensus

A more representative way to VOTE.

(an expanded version is available as a APSA working paper)

The promise of “representative majority rule” remains a corner-stone of democracy, but this ideal is often under-mined in a“first-past-the-post” (FPTP) election. When three or more candidates compete and voter preferences are split — an all-too-common occurrence — the winner is determined by a mere plurality, rather than a true majority, of votes. As a result, a niche candidate, supported by only one-third of voters, can end up representing an entire district — casting doubt on the democratic legitimacy of the outcome. Even more concerning, vote splitting induced by spoiler candidates can lead to the defeat of a consensus candidate — one whose policies reflect a clear majority preference.

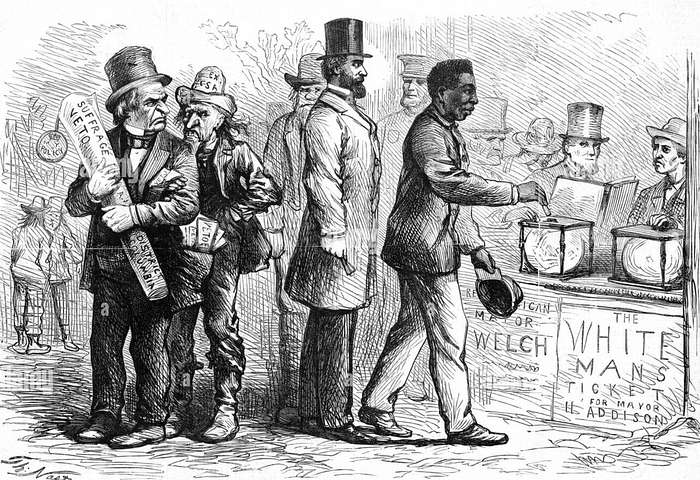

A democracy without fair representation is a democracy in name only — see:

To address these inequities, Ranked Choice or Preference Voting (RCPV) methods have been proposed and, in a few cases, adopted. Here, voters declare their 2nd, 3rd, etc. choice candidates on the ballot. If no candidate receives a majority on the initial round of voting, their preferences are automatically applied to alternate candidates in the second round, and so on until a synthetic majority winner is declared. Thus you can vote your conscious while voting pragmatically at the same time.

Which makes sense, in principle.

But RCPV demands voters invest the time, knowledge and interest to pre-record their alternate choices for subsequent automatic vote-preference reallocation. It’s hard enough to pick a single favorite candidate from a large field, let alone justify a third and fourth choice among similar or unknown candidates.

While intellectually fascinating to design and debate, RCPV systems can also be opaque and complex. Lazy or misguided voters can undermine even the most carefully planned voting schemes. Dishonest voters may try to “game” the system by strategically de-rating hated political rivals. Or the algorithm can misfire, leading to sometimes embarrassing disconnects between election results and common sense.

Despite thousands of years of experimentation, no universally acceptable RCPV system has emerged that can challenge FPTP. Worse yet, proponents of each RCPV sect may share the same democratic goals, yet argue vigorously against each other, further muddying the electoral waters⁸.

As an alternative to RCPV and FPTP we can take our inspiration from an 1880’s suggestion by Charles Dodgson¹ (Lewis Carroll). Let the candidates themselves reallocate votes until a majority winner emerges.

We call this proposal Negotiated Consensus (NC). In the absence of a simple majority after election day, the candidates negotiate, for a concession, to transfer all (or some) of their votes to other aspirants. With NC, you vote for your preferred candidate, grant them your proxy, and trust them to reach an accord on your behalf during real-time, post-election negotiations. Similar to forming a ruling coalition in a parliamentary system. Any candidate accumulating a majority of the votes, including pledged transfers, wins.

Unlike RCPV (see next section) where your alternate-votes are given away having received nothing tangible in return, in NC small parties gain influence for their constituents during negotiations. Perhaps swapping votes for a future cabinet seat. Or agreeing to pick-up support by softening their position on climate adaptation.

The pattern of these negotiations will vary from election to election. In some cases, where there are two main contenders and a third party candidate with similar views to one of the leaders, the smaller constituency will transfer their votes in exchange for a policy concession. With five candidates and three leaders, negotiations will be more intense and the concessions greater. Forcing the winner to align more closely to the electorate. A plus for democratic representation.

No doubt small parties may prove to be intransigent, and larger parties arrogant. But the risk of losing the election because your opponent assembled a majority coalition will bring everyone to the table.

What happens if an agreement cannot be reached? Certainly, public pressure will increase, but if after three weeks there is no winner, the top two candidates (after any vote transfers) hold a runoff election. Unlike conventional runoff elections where the top two are merely plurality leaders, in NC vote transfers may determine the top candidates. Third-party influence is baked into the runoff. This should also encourage small party voters to vote in the runoff as they now have a direct stake in the outcome.

NC eliminates the spoiler effect, disingenuous clones, plurality winners, mathematical voting aberrations, complexity and wasted votes. Negotiations force compromise and, over time, the pragmatic candidate’s best tactic is to behave more like a virtuous representative.

How does one compare voting systems in a democracy? There is no generally accepted legal or political answer. Political scientists often defer to some kind of general “satisfaction” with the outcome as a metric. The democratic goal is maximizing election satisfaction (presumably with at least a majority of the voters).

It is possible for 70% of the voters to be satisfied despite the winner only garnering 55% of the votes, as the losers might still agree the election was fair. The converse is also true- 40% could be satisfied even though they voted for the majority winner, because they preferred a different candidate as their standard bearer and thought the primary system was corrupt.

In the spirit of maximizing representation and voter satisfaction, ranking systems are generally designed to improve the chances of independent or smaller parties participating and winning. Studies also indicate enhanced competition slightly encourages candidates to become more moderate or centrist, but unless moderation improves overall voting satisfaction, this is a side-effect and not a democratic goal.

Among the dozens of proposed voting systems two seem closest to adoption: some variation on the theme of Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) or Ranked Preferences (RP).

There are numerous technical and practical issues with RCV (see link for an RCV tutorial, it can get complicated). Because the vote-aggregation steps are non-linear, you cannot simply sum the outcomes from different precincts, but must wait until all votes are certified and merged. This can delay or call into question the outcome. Standard voting machines are not suited for RCV, so a few percent of people regularly spoil ballots by inadvertently declaring two second choices (and a few percent may be critical in tight elections). Exhausted ballots, where the automated process could not match a voter to the final two contenders due to the order of their choices, may disenfranchise 10% to 15% of the electorate.

RCV has failed in the field, for example, in the 2009 Burlington, VT mayoral election neither the plurality or the head-to-head preferred candidate won, leading to low voter satisfaction with the result. RCV was repealed later that year.

RCV may also prematurely eliminate the consensus candidate, which, to the extent they are the candidate satisfying most voters, implies the least democratic choice won. For example, imagine Alex receives 38% of #1 votes, Blake 35% and Carey 27%. No one has a majority on the first round, so an automated reallocation occurs. Alex’s and Blake’s voters hate each other’s guts, so only a few will rank each other as #2, but they generally approve of Carey. However, in RCV, after each round the bottom vote-getter is dropped, which means the consensus candidate Carey loses. True, Carey’s second-choice selections will tip the election in a direction they prefer, but fewer people will be happy with that outcome compared to Carey winning. This effect is only amplified when there are spoiler or clone candidates splitting narrow differences so the consensus candidate keeps falling to the bottom and is eliminated.

There is also an existential question. Is your #2 ranked candidate slightly worse than #1, or just over the bar? In either case they receive a fully-transferred vote on the second round, which may over or under-estimate voter intent. That is, if maximizing voter satisfaction is the goal, should two lukewarm #3 votes be worth twice as much as one strong #2?

STAR voting, a form of Ranked Preferences, was invented to avoid many of these aberrations, and is often compared to submitting a Yelp review. In STAR you don’t rank the candidates against each other, but instead compare individuals to an abstract concept of “goodness” on a five-point scale. Similar to a restaurant review, where you rate your experience compared to an ideal meal, not directly to other restaurants. Instead of averaging, the rankings are weighted by the number of diners. So, a restaurant with 100 five star reviews gains 500 points, while one with 1000 four stars are assigned 4000 points. And thus wins the “Best Of” award. Note the more popular establishment may not actually serve the best food, but satisfies the most people most of the time. Democracy in action.

Unlike Yelp, the “AR” in STAR stands for “Automatic Runoff”. After the preference scoring round, the top-two highest scorers are compared in an instant-runoff re-using earlier preference scores, winning points for every head-to-head ballot with a higher preference. The head-to-head winner is elected.

Since all preferences are combined before candidates are compared, every vote counts and there are no exhausted ballots in the scoring stage. However, if you did not indicate a relative head-to-head score for the eventual runoff candidates, or scored them identically, your ballot has no effect in the runoff. So effectively an exhausted ballot.

In STAR, voters assign preferences from 5 to 1 to each candidate, and thus each step in preference is downgraded by 20% when preferences are averaged. But why 20% and uniform steps, except for mathematical ease? Depending on the degrading factors between levels, different candidates can win.

Dishonest voting is an issue, as are clones and collusion. In addition, the “stars” have no fixed meaning. Similar to RCV, combining preferences is problematical where each voter had a different scale in mind.

Moreover, as with all automatic voting systems, ranks/prefs are preloaded into the system BEFORE voters are aware of the results of the first round. In principle, responsible voters should be able to pre-rank their choices accurately and let the math output a decision. But as Samuel Johnson noted ‘Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.’ Often people vote their emotions, won’t rank logically, and when they finally realize their emotional position led to an idiot winning, regret their passion.

Advantages of Negotiated Consensus:

- Can vote your conscious and still influence the outcome via your proxy. In response, small parties will emerge and grow in strength.

- No wasted ballots.

- No exhausted ballots.

- Easy to understand- no fancy math or obscure weighting and transfer rules. No need to make fine-grained ranking distinctions between candidates, where none logically exists.

- Works with standard voting machines.

- Linear, so votes can be validated and combined at a district level.

- Small parties are unlikely to win, but may help decide an election in exchange for key concessions. So third-parties gains indirect political representation well beyond the shadow effect in RCPV.

- Spoiler and clone effects minimized during vote transfer negotiations- those with similar political interests are strongly incentivized to work together. Two or three smaller parties could club their votes together, settle upon a consensus candidate and policies, and win the election.

- Candidates can poll their voters during negotiation (who now have a better understanding of practical alternatives) and adjust their vote accordingly.

- Proxy transfers create a true majority winner.

Issues with Negotiated Consensus:

- Perhaps illegal in some jurisdictions, and certainly unfamiliar. Will definitely raise red flags.

- The cost of holding a potential runoff.

- Possibly lower turnout in the runoff (then again, possibly higher as is typical with primaries vs regular elections).

- Vote buying and collusion is possible, but if you don’t trust your candidate in NC, you won’t trust them in office.

- Small parties may be thrust into the role of “king makers”. But larger parties can moderate this tendency if they agree to cooperate. Or default to runoff.

- Candidates might renege on a promise, but assuming elections are held again in a few years, they will have no credibility in future negotiations. So, everyone has an enormous incentive to honor their commitments. Classic game theory.

- As in many voting systems, a minimum level of support may be required to qualify for the ballot- perhaps via a primary or enrollment stage to weed out niche parties.

- It will take a number of election cycles for the party system to adapt and for new parties to coalesce. Voters may lose patience in the interim.

- Americans expect a winner will be announced the day after the election, and initially may be uncomfortable with NC’s longer time horizon.

Random Variations in Negotiated Consensus:

Note any rigid forcing-function to break an NC deadlock, such as an instant runoff or preference vote, will be gamed by candidates in their favor. For example, if you knew you would win a runoff you have no incentive to negotiate vote transfers in good faith.

A compelling but unconventional alternative is Athenian randomness (see article). If after three weeks there is no consensus winner, instead of facing each other in a runoff election, one of the top three (after transfers) candidates wins by random selection.

Sortition is hard to game, and is rough justice. But I fear injecting intentional randomness into an election will be a hard sell, no matter how efficacious. So NC defaults to a top-two runoff election.

Multi-member Districts and Negotiated Consensus:

A similar approach can be used in multi-member districts. Let’s say there are three open positions and a dozen candidates. Each voter has three votes they can apply entirely to one, or split among two or three candidates. Any candidate who can win or gain transfers of 25%+1 of the total cast votes (the Borda threshold, basically a majority criteria) is provisionally elected. Any excess can be transferred to others.

Again, multi-member negotiations will determine the outcome. Rather than decreasing the chance of compromise, sometimes more people at the table enables pragmatic tradeoffs. As President Eisenhower once remarked “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger”. More voices, more degrees of freedom.

In the event one or more seats are unfilled after three weeks, a runoff election is held. The runoff must include the candidates who already passed the 25% threshold, and the top two or three of the remainder (two, if two candidates achieved the threshold, three if only one).

Why are the “winners” of the first round included in the runoff? To avoid the tyranny of the majority. If the winners of the first round are excluded, then the largest plurality basically double-dips, knowing their preferred candidate is already safe . In fact, a large plurality might discourage negotiations to throw the election into a runoff- instead of splitting the seats, as they could win every seat unless included in the runoff.

Alternatively, a random winner could be selected from among the top two (or three) to fill any open seats not above the Borda threshold. Avoiding the cost and complexity of a runoff.

Useful References:

[1] Charles Dodgson, aka Lewis Carrol, was fascinated by voting system design. He invented some of the earliest proportional voting methods, and balanced mathematical optimization methods with real-world concerns over voting privacy and manipulation. There was even an “NC”-like feature involving the formation of coalitions:

May I, in conclusion, point out that the method advocated in my pamphlet

(where each elector names one candidate only, and the candidates themselves can, after the numbers are announced, club their votes, so as to bring in others besides those already announced as returned) would be at once perfectly

simple and perfectly equitable in its result?C. L. Dodgson, The Principles of Parliamentary Representation: Supplement (Oxford 1885), p7.

[2] NC is a variation of “Asset Voting”, which like NC, has been independently reinvented a number of times. It is also loosely related to proxy voting. As always, the devil is in the details.

[3] Australian elections are predominately a form of RCV. Parties, after mutual negotiations and strategizing, issue “cheat sheets” (how-to’s) to guide their member’s ranked selections in the voting booth. But compliance only runs from 20% to 50%.

[4] Jobst Heitzig and Forest W. Simmons propose a nice mathematical stochastic voting method allowing minorities to gain leverage when reaching consensus.

[5] https://blog.yelp.com/news/new-study-compares-yelp-review-quality-with-competitors/

[6] The mathematical-political papers of C. L. Dodgson, 1982 Francine Abeles, in Lewis Carroll, a Celebration ISBN 13: 9780517545577

[7] Parties often run spoiler candidates intended to draw votes away from their opponent. For example, candidates R and D are in a close race, but D is ahead. So R supports a candidate with similar views to D and surreptitiously helps them qualify for the ballot. This mini-D candidate draws votes from D, and suddenly R is the plurality winner! Frustrating the majority-will of the people for a D-style winner.

Spoilers put their thumbs on the scale in tens of thousands of local races, and at least five US presidential elections.

[8] For example, in 2024 STAR Voting campaigned against RCV in Oregon. And FairVote replies in kind.